Pierre Narcisse Guérin (1774-1833), French, Morpheus and Iris, 1811, oil on canvas, 251 x 178 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Can’t sleep? Worried that you’ll miss the rainbow goddess, Iris, when she appears in the morning or maybe appear a bit more dishevelled than Morpheus in Guérin’s painting?

Music can help you sleep. It is a time-honoured tradition. Musicians performed nearby when Louis XIV decided to go to bed at night. Marin Marais composed some Trios for the Sung King’s bedchamber.

One of the first stories about music and insomnia involves the charming story about Bach’s Goldberg Variations (BWV 988). The composer wrote the great work for a Count Kaiserling, an ambassador of the Russian Imperial Court to the Elector of Saxony’s Court. Kaiserling was afflicted with insomnia. Wherever he travelled, his young harpsichordist, Johann Goldberg, travelled with him to play music during the night while the Count tried to sleep. Bach wrote the piece for Goldberg, essentially a theme with 30 variations, to entertain the Count. His Grace was delighted and rewarded Bach handsomely. A nice story, but alas, it seems to be a fabrication of one of Bach’s early biographers (1802), half a century after Bach’s death in 1750. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldberg_Variations)

In our marvellous digital age, you too can have a virtual Johann Goldberg playing these variations on, say, your bedside Amazon Echo device. In fact, you can use your musical time machine to conjure up a host of other musicians from different periods to add to Mr Goldberg’s musical entourage.

So the question is, what constitutes a viable playlist for the insomniac? The objective is to somehow induce rest, if not sleep. The Goldberg Variations are familiar to most people who like classical music. There are many, many recorded versions of the work! Some are more exciting than others. I am not sure that listening to the two extraordinary recordings (1955 and 1981) of the work by Glenn Gould would be that relaxing. In fact, they make for pretty exciting listening. My preference for the purpose at hand is a version played on the harpsichord, the quieter the better. For this purpose, volume control comes in handy. My preference is Joseph Payne’s 1991 recording on BIS CD-519.

So the question is, what constitutes a viable playlist for the insomniac? The objective is to somehow induce rest, if not sleep. The Goldberg Variations are familiar to most people who like classical music. There are many, many recorded versions of the work! Some are more exciting than others. I am not sure that listening to the two extraordinary recordings (1955 and 1981) of the work by Glenn Gould would be that relaxing. In fact, they make for pretty exciting listening. My preference for the purpose at hand is a version played on the harpsichord, the quieter the better. For this purpose, volume control comes in handy. My preference is Joseph Payne’s 1991 recording on BIS CD-519.

Staying with Bach for a moment, my next choice would be a recording of his Art of the Fugue (BWV 1080). Bach did not specify the instrumentation for this unfinished work, so many resourceful performers have come up with their own approaches. The Art of the Fugue is essentially an exercise in counterpoint. Like the Goldberg Variations, the various canons and fugues can sound rather mathematical. My choice is a bit idiosyncratic, keeping in mind the context of insomnia. It is the version performed by the Canadian group Les Voix Humaines, a consort of viols, in this case, four of them. (ATMA Classique (ACD2-2645). If you are used to a more direct and literal interpretation of the score, this will come as a surprise. The historical context of viol playing (French and British) is brought to bear on the performance, with lots of ornamentation, so that the score is used more as a roadmap than a score, and there is a sense of archaic improvisation, but the key is the sound produced. It is one of my favourite recordings to play on my Amazon Echo device in the middle of the night.

Staying with Bach for a moment, my next choice would be a recording of his Art of the Fugue (BWV 1080). Bach did not specify the instrumentation for this unfinished work, so many resourceful performers have come up with their own approaches. The Art of the Fugue is essentially an exercise in counterpoint. Like the Goldberg Variations, the various canons and fugues can sound rather mathematical. My choice is a bit idiosyncratic, keeping in mind the context of insomnia. It is the version performed by the Canadian group Les Voix Humaines, a consort of viols, in this case, four of them. (ATMA Classique (ACD2-2645). If you are used to a more direct and literal interpretation of the score, this will come as a surprise. The historical context of viol playing (French and British) is brought to bear on the performance, with lots of ornamentation, so that the score is used more as a roadmap than a score, and there is a sense of archaic improvisation, but the key is the sound produced. It is one of my favourite recordings to play on my Amazon Echo device in the middle of the night.

There is something mesmerizing about the sound of a consort of viols, even a mere pair of viols, and fortunately, there is quite a large repertoire of music for two or more viols. Staying with Les Voix Humaines, they have recorded the complete works of Jean de Sainte-Colombe for 2 bass viols on no less than 8 CDs. It is extraordinary stuff. The music of Sainte-Colombe was introduced to a wide public in the 1991 film Tous les Matins du Monde. Any of these albums could be used in the insomniac’s playlist. And they have recorded a lot more viol music. For English viol music, Henry Purcell’s Fantasias for viols are quite extraordinary.

There is something mesmerizing about the sound of a consort of viols, even a mere pair of viols, and fortunately, there is quite a large repertoire of music for two or more viols. Staying with Les Voix Humaines, they have recorded the complete works of Jean de Sainte-Colombe for 2 bass viols on no less than 8 CDs. It is extraordinary stuff. The music of Sainte-Colombe was introduced to a wide public in the 1991 film Tous les Matins du Monde. Any of these albums could be used in the insomniac’s playlist. And they have recorded a lot more viol music. For English viol music, Henry Purcell’s Fantasias for viols are quite extraordinary.

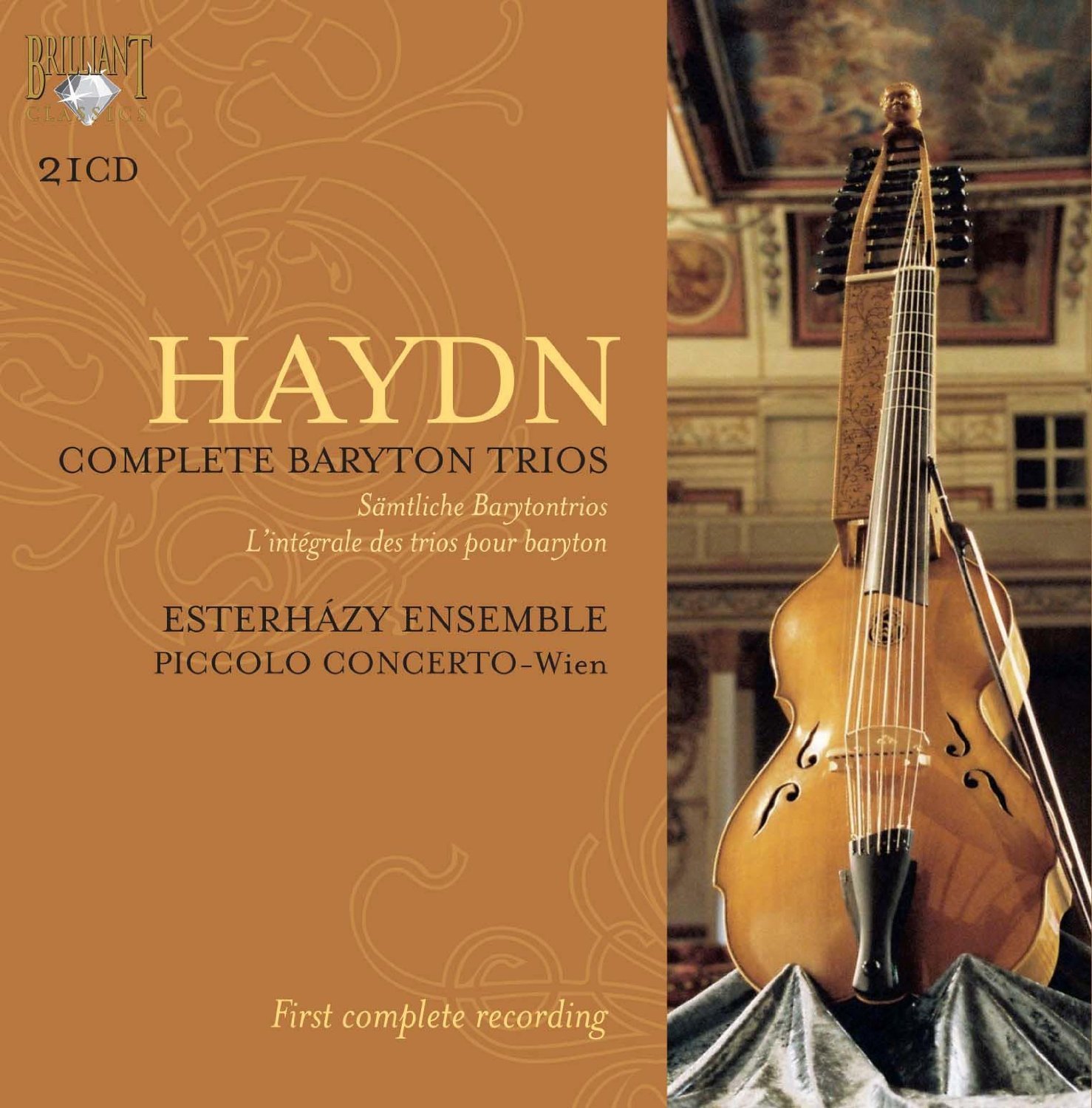

A contemporary relative of the viola da gamba was the baryton. Because Prince Nicholas Esterhazy happened to play this instrument, his resident composer, Joseph Haydn had to compose music for the Prince and his instrument. As a result, there are over a hundred trios for baryton, viola and cello. These are very mellow instruments, and the baryton trios are remarkable. Fortunately, there has been a bit of a revival of interest in the baryton as a result of the contemporary predilection for music played on original (or authentic) instruments. In 2009, one ensemble even recorded everything that Haydn wrote for the instrument, and as I am a great fan of Haydn, I bought the entire set. Some say it is boring music, but I love it. The entire set is available on Spotify Premium, the best service if you love classical music and a tremendous resource for compiling a customized playlist for the insomniac. (For Classical music, Amazon Prime Music is useless!) Haydn’s baryton trios suit the bedside playlist really well. There are examples of Baryton Trios by Hadyn on YouTube, where you can see and hear this rare and resonant instrument.

A contemporary relative of the viola da gamba was the baryton. Because Prince Nicholas Esterhazy happened to play this instrument, his resident composer, Joseph Haydn had to compose music for the Prince and his instrument. As a result, there are over a hundred trios for baryton, viola and cello. These are very mellow instruments, and the baryton trios are remarkable. Fortunately, there has been a bit of a revival of interest in the baryton as a result of the contemporary predilection for music played on original (or authentic) instruments. In 2009, one ensemble even recorded everything that Haydn wrote for the instrument, and as I am a great fan of Haydn, I bought the entire set. Some say it is boring music, but I love it. The entire set is available on Spotify Premium, the best service if you love classical music and a tremendous resource for compiling a customized playlist for the insomniac. (For Classical music, Amazon Prime Music is useless!) Haydn’s baryton trios suit the bedside playlist really well. There are examples of Baryton Trios by Hadyn on YouTube, where you can see and hear this rare and resonant instrument.

In the same period that Haydn composed his music, during his short life Mozart also wrote some night music, but his brilliant Eine Kleine Nachtmusic, K. 525 (1787) is a little too energetic for our purposes. For something a bit more suitable, his music for Basset Horns will do admirably. I am fortunate enough to have a 1986 recording of such music played by the Cleveland Symphony Winds (CBS Masterworks M2K42144). What is particularly marvellous about this recording is that the various notturnos and divertimentos are arranged in programs where the notturnos (sung by male or female voices with basset horn accompaniment) alternate with the instrumental divertimentos, usually scored for three basset horns. While I don’t advise vocal music to put you to sleep, lullabies notwithstanding, this would at least relax you. There are a few other Notturnos by Mozart, but they are actually quite boisterous affairs, suitable for a very civilized evening garden party.

In the same period that Haydn composed his music, during his short life Mozart also wrote some night music, but his brilliant Eine Kleine Nachtmusic, K. 525 (1787) is a little too energetic for our purposes. For something a bit more suitable, his music for Basset Horns will do admirably. I am fortunate enough to have a 1986 recording of such music played by the Cleveland Symphony Winds (CBS Masterworks M2K42144). What is particularly marvellous about this recording is that the various notturnos and divertimentos are arranged in programs where the notturnos (sung by male or female voices with basset horn accompaniment) alternate with the instrumental divertimentos, usually scored for three basset horns. While I don’t advise vocal music to put you to sleep, lullabies notwithstanding, this would at least relax you. There are a few other Notturnos by Mozart, but they are actually quite boisterous affairs, suitable for a very civilized evening garden party.

Then there is Schubert, whose exquisite melodies will provide rest and delight. None more so than his Notturno in E flat major (D.897). Several wonderful versions of this. My favourite is one performed by the Gryphon Trio in their Analekta compilation of Great Piano Trios by Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert and Shostakovich. There is a fairly loud middle section but quiet prevails in the end.

It seems natural to link insomnia with nighttime, and in a musical context, it is the Nocturne (Notturno) that first comes to mind when thinking of night music. As a rule, a nocturne will be quiet and slow. The Romantic period provided music lovers with splendid nocturnes, of which 16 were composed by the Irish musician John Field between 1812 and 1836. Well known as a performer in his time, Field seems to have originated the Nocturne as a composition for solo piano. Field’s Nocturnes were much admired by his more famous contemporary, the Polish musician Frédéric Chopin, who would write 21 Nocturnes between 1827 and 1846. Both Field’s and Chopin’s Nocturnes are perfect music for the insomniac. Lots of recordings of the Chopin Nocturnes. I have had Daniel Barenboim’s interpretations for years, but have found much delight in a recent recording found on Spotify by François Dumont. It has soothed me to sleep many times, before the 1 hour and 43 minutes have played through.

It seems natural to link insomnia with nighttime, and in a musical context, it is the Nocturne (Notturno) that first comes to mind when thinking of night music. As a rule, a nocturne will be quiet and slow. The Romantic period provided music lovers with splendid nocturnes, of which 16 were composed by the Irish musician John Field between 1812 and 1836. Well known as a performer in his time, Field seems to have originated the Nocturne as a composition for solo piano. Field’s Nocturnes were much admired by his more famous contemporary, the Polish musician Frédéric Chopin, who would write 21 Nocturnes between 1827 and 1846. Both Field’s and Chopin’s Nocturnes are perfect music for the insomniac. Lots of recordings of the Chopin Nocturnes. I have had Daniel Barenboim’s interpretations for years, but have found much delight in a recent recording found on Spotify by François Dumont. It has soothed me to sleep many times, before the 1 hour and 43 minutes have played through.

Maybe just reading this soporific text has already put you to sleep, but there are a couple of more contemporary works I have to mention. A number of years ago, I became intrigued by Federico Mompou’s Musica Callada. (1959-67) I had never heard of this Catalan composer before, let alone this extraordinary music. The very idea of “silent music,” was challenging, so I purchased his complete piano works performed by the composer himself. Not being a musicologist, I can’t quite describe the Muisca Callada adequately, except that it is strangely riveting, very quiet music, hypnotic in effect. Lately, I have been playing a wonderfully sensitive performance, again found on Spotify, by Emili Brugalla.

Maybe just reading this soporific text has already put you to sleep, but there are a couple of more contemporary works I have to mention. A number of years ago, I became intrigued by Federico Mompou’s Musica Callada. (1959-67) I had never heard of this Catalan composer before, let alone this extraordinary music. The very idea of “silent music,” was challenging, so I purchased his complete piano works performed by the composer himself. Not being a musicologist, I can’t quite describe the Muisca Callada adequately, except that it is strangely riveting, very quiet music, hypnotic in effect. Lately, I have been playing a wonderfully sensitive performance, again found on Spotify, by Emili Brugalla.

Another piece of extraordinary contemporary music is John Tavener’s, The Last Sleep of the Virgin (1991). It was composed on the eve of the composer’s major heart surgery. He specified that the players were to perform the piece “at the threshold of audibility.” It is scored for string quartet and handbells, and the effect conveys a trance-inducing sound. (The companion piece on this particular recording, The Hidden Treasure, is not conducive to sleep).

Another piece of extraordinary contemporary music is John Tavener’s, The Last Sleep of the Virgin (1991). It was composed on the eve of the composer’s major heart surgery. He specified that the players were to perform the piece “at the threshold of audibility.” It is scored for string quartet and handbells, and the effect conveys a trance-inducing sound. (The companion piece on this particular recording, The Hidden Treasure, is not conducive to sleep).

Arvo Pärt is apparently the most performed contemporary composer in the world today. Born in Estonia, his music evolved into something simple and extraordinary. I first heard his music more than a decade ago. Then a friend lent me his newly-purchased copy of Spiegel am Spiegel and Alina. I immediately bought the CD even before returning my borrowed copy. The work has been recorded many times, but this particular recording is the treasure. And it has lulled me to blissful sleep more often than any other music. It is still the Pärt CD I play most often, and I have several, even some earlier works recorded on BIS.

Arvo Pärt is apparently the most performed contemporary composer in the world today. Born in Estonia, his music evolved into something simple and extraordinary. I first heard his music more than a decade ago. Then a friend lent me his newly-purchased copy of Spiegel am Spiegel and Alina. I immediately bought the CD even before returning my borrowed copy. The work has been recorded many times, but this particular recording is the treasure. And it has lulled me to blissful sleep more often than any other music. It is still the Pärt CD I play most often, and I have several, even some earlier works recorded on BIS.

All of these recordings are my current choices to induce sleep. In another time, I am sure I would have chosen others. There would have been more orchestral music in all probability. Probably much Gregorian chant which I have always loved. But given current technology and resources (Amazon Echo, Spotify Premium), these recordings are on my present list, enough to keep you in your bed at night, and enough to bring you into the arms of Morpheus.

©Roger H. Boulet

10 April 2018.

All among my favourites, but not because I have insomnia.

LikeLike