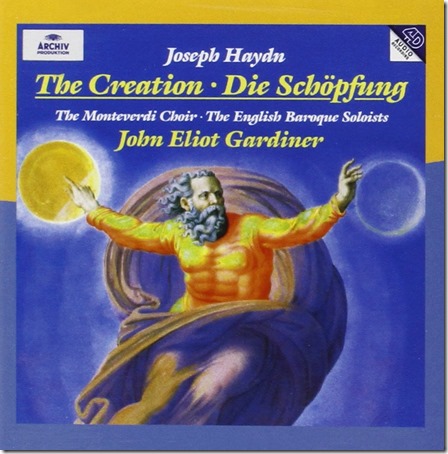

Claude Lorrain: Port Scene with the Embarkation of St Ursula, 1641, Oil on canvas, 113 x 49 cm, National Gallery, London

In a previous blog [4 February 2015], I was writing about J.W.M Turner after seeing the movie, Mr. Turner. His connections with Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) in particular have always been interesting to me. If any painter epitomizes the idea of ‘the Beautiful,’ it is certainly Claude Lorrain and his serene sunlit landscapes and seascapes. We are taken nowadays more by the beauty of the landscapes than we are by the narratives that are their pretext. This was a time when pure landscape painting was deemed a lower form of art, hence the obligatory narratives from classic authors and the Bible, to provide that necessary moral content that made pure delight more permissable.

In considering Turner, I can’t help but looking at the work of his predecessor, a French artist, Joseph Vernet (1714-89) also much inspired by his illustrious predecessor Claude Lorrain. Both artists worked in Rome to a greater or lesser extent. Lorrain virtually spent his whole life there, while Vernet made his way to Rome in his teens, and only returned to France when his fame had been firmly established. He came to specialize in seascapes, or marine painting as it is also called, and therefore a comparison to Lorrain’s luminous seascapes done a century earlier is certainly in order. With Lorrain, Vernet and Turner we cover almost three centuries of landscape painting in Europe, although we must also mention the landscape and seascape tradition in the Netherlands in the 17th century, especially when discussing Turner.

Here is a typical work by Vernet, and a great one at that. It is a worthy introduction to this relatively little known artist, at least as far as the general public is concerned. It also provides a good example of the type of work that made Vernet’s work so much in demand.

Joseph Vernet: Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, 113.5 × 162.9 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

From the serenely beautiful landscape by Claude Lorrain, depicting the Embarkation of St. Ursula, (above) to the stormy scene with shipwreck, we are introduced to a different aesthetic, and it is that of the Sublime. Rather than explaining what the Sublime is, I will simply link to an excellent Wikipedia article on the subject. The concept was widely disseminated, especially after Edmund Burke wrote his little essay on the subject, which he entitled A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful. It first appeared in print in 1757. A single quote will be sufficient to explain what the Sublime was all about, certainly as far as landscape painting is concerned.

“Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling …. When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and [yet] with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful, as we every day experience.”

Just looking at that Vernet and the terror of a shipwreck and a storm at sea would be enough to bring about a little frisson in the viewer.

But Vernet wasn’t all about shipwrecks and stormy seas. It seems that a couple of times at least, he painted cycles of seascapes depicting various times of day, accompanied by various appropriate activities ashore carried on by common folk. No need to evoke the Embarkation of St. Ursula, or the Trojan Women Burning their Ships, as Claude Lorrain felt was necessary.

Here is the cycle of four paintings by Vernet depicting those times of day.

Joseph Vernet: The Four Times of Day: Morning, 1757, oil on silvered copper, 29.5 x x 43.5 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Here, fishermen are seen on their boat in the early morning with their catch.

Joseph Vernet: The Four Times of Day, Midday, 1757, oil on silvered copper, 29.5 x x 43.5 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

An unexpected storm surprises people ashore, including fishermen tending a net.

Joseph Vernet: The Four Times of Day, Evening, 1757, oil on silvered copper, 29.5 x x 43.5 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Women are seen bathing and washing clothes in a river or an inlet, in the evening, as shadows begin to fill the valleys as the sun declines.

Joseph Vernet: The Four Times of Day, Night, 1757, oil on silvered copper, 29.5 x x 43.5 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Night falls. Some fishermen are drying their nets, as others warm themselves by a fire, while moonlight shines over a calm sea.

A number of things can be mentioned about these works. Their setting is an imaginary one, perhaps inspired by the Italian coast. Their medium and support of ‘oil on silvered copper’ is an interesting departure from the usual oil on wood panel, and there are a number of reasons why artists used this during the 17th and 18th centuries. There was minimum shrinkage of the support due to changing ambient temperatures so the paintings did not crack. Also, the silvered copper support seemed to facilitate a luminous effect, and for a painter like Vernet, this would have been important. The relatively small size of the works makes more sense in terms of the use of a silvered copper plate as a support. Vernet’s work is most often encountered in larger dimensions, and there, a stretched canvas provides a better support… although somewhat more subject to cracking and crazing.

The depiction of various times of day indicates that artists were making studies in nature, and their observations informed their work. Even Claude Lorrain and his colleague Nicolas Poussin often made studies in the Roman countryside. They were sensitive to the different characteristics of light during different hours of the day.

The stormy seas and dramatic skies were certainly one of Vernet’s specialties. Not unusually, much of the painting is devoted to the painting of the sky, and this certainly appealed to the emotions as well as to the contemporary interest in science and its observation of natural phenomena. Vernet painted during a period known as the Enlightenment, where new attention was paid to scientific study and empirical data. During Vernet’s lifetime, the first Encyclopédie (1751) was published in France, and writers and philosophers such as Diderot, d’Alembert, Voltaire and others, were expressing their doubts about all aspects of knowledge as transmitted through the study of ancient texts. It was the beginning of a new era. In one sense, the storms of Vernet express that the ideal of serene beauty was being successfully challenged.

- Joseph Vernet: A Stormy Sea, 1748, Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 60.5 cm, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Vernet’s life spans the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI, the former coinciding with the period known as the Roocco, the latter witnessing the rise of Neoclassicism. But during the last half of the 18th century, Romanticism was coming to the fore, first in a German movement known as Sturm und Drang, and then in the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. One of Vernet’s last works, now in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg is entitled the Death of Virginie, and was inspired from a reading of one of Romanticsm’s earliest novels, Paul et Virginie by Bernardin de St. Pierre, first published in 1788, the year before Vernet’s death.

- Joseph Vernet: La Mort de Virginie, 1789, oil on canvas, 87 x 130 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- I suspect the painting could use a good cleaning or a better reproduction. Nevertheless, here is nature dominating the affairs of humanity through its unimaginable power. The idea of the course of life as a succession of calm days and frightening storms, of moments of discovery, and moments of doubt, even of despair is no doubt what Vernet’s patrons were responding to, and in many ways, it is how we respond to these works today, if we look at these works in the context in which they were created.

- © Roger H. Boulet, 2015